Seeing Beyond Sight: Andrew Leland's Journey Through Blindness

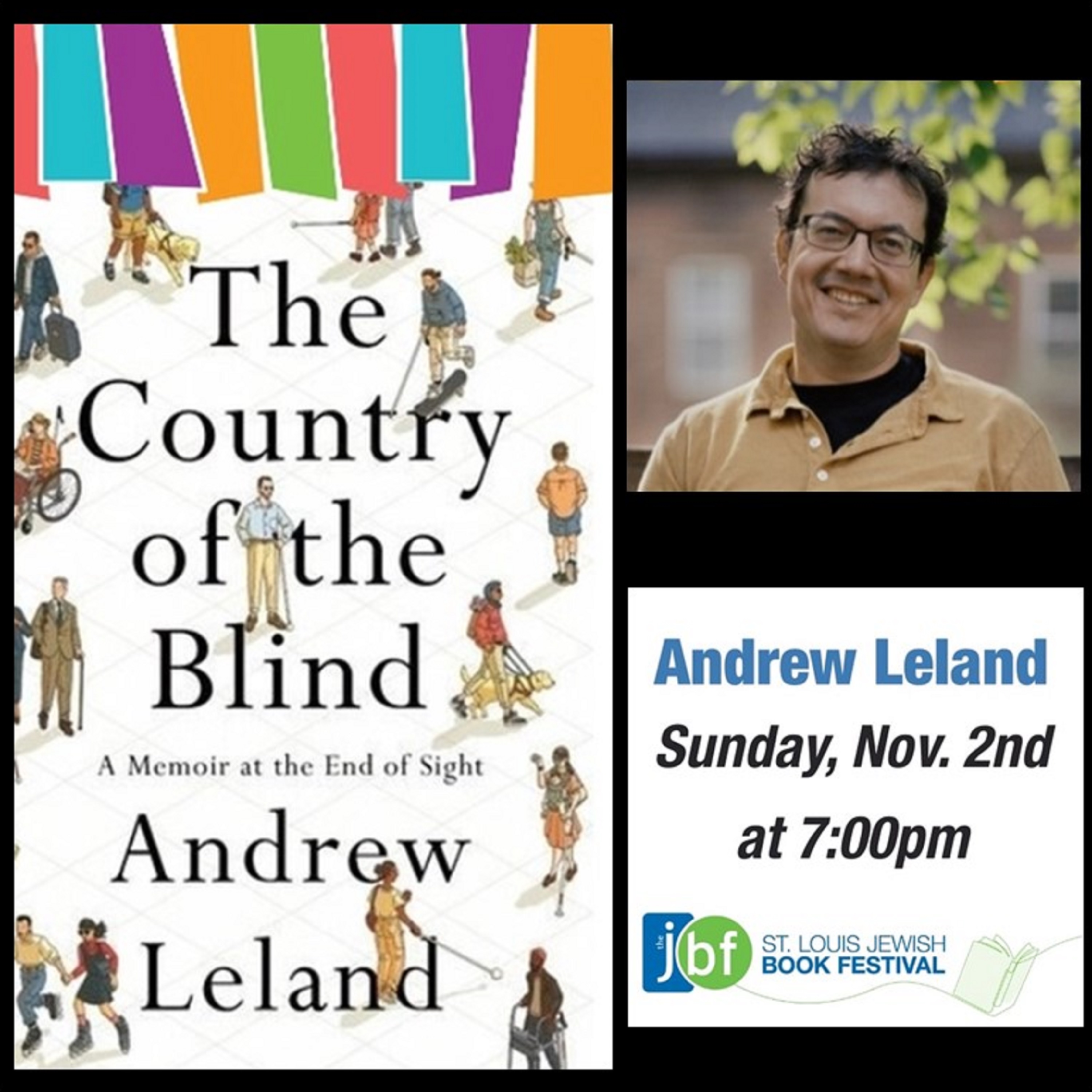

Andrew Leland joins us to converse about the world of blindness and the profound journey he's been on while navigating his own retinal degeneration. His book, "The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight," isn't just an exploration of what it means to lose one’s vision; it's a candid look at the societal perceptions surrounding disability and the misconceptions that often accompany it. Don’t miss his upcoming talk at the Carl and Helene Mirowitz Performing Arts Center on November 2nd—this is one conversation you won't want to miss!

Andrew Leland joins us for a deeply engaging chat about his life and his memoir, The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight. This isn't just any old memoir; it's a journey through the intricate layers of navigating life as someone experiencing blindness. Picture this: Andrew, a writer and audio producer, begins to lose his sight but instead of retreating into darkness, he dives headfirst into the vibrant world that opens up when you start to see beyond vision.

We explore his personal milestones—like the moment he picked up a white cane and the whirlwind of social dynamics that followed. Suddenly, he wasn't just Andrew; he was 'the blind guy', and that title brought with it a flurry of assumptions, expectations, and a hefty dose of pity. But Andrew is not one to let societal labels define him. He shares how blindness is often a conversation starter for deeper philosophical questions about perception, ability, and what it means to 'see'.

As our discussion unfolds, Andrew shares insights about the misconceptions surrounding blindness, the tech that empowers blind individuals today, and how acceptance can be a liberating force. Get ready for a thought-provoking episode that challenges the way we perceive disability, featuring Andrew’s witty commentary and sharp reflections on the human experience..

[00:00] Introduction and Welcome

[00:45] Meet Andrew Leland: Author and Advocate

[01:37] Living with Retinitis Pigmentosa

[05:33] Social Perceptions and Stigma

[11:31] Technology and Accessibility

[17:02] Defining Blindness and Acceptance

[25:37] Andrew's Journey and Future Plans

[27:47] Conclusion and Farewell

Takeaways:

- Andrew Leland shares his journey with retinitis pigmentosa, exploring how it affects his vision and life.

- The conversation dives into societal perceptions of blindness and the stigma surrounding disabilities, revealing personal stories.

- Leland emphasizes the importance of assistive technologies, like braille and screen readers, for blind individuals.

- The impact of using a white cane transforms Andrew's social experience, changing how people interact with him.

- Leland discusses misconceptions about blindness, highlighting that blind people can still be tech-savvy and independent.

- His memoir reveals the philosophical questions surrounding perception, disability, and identity, making it a thought-provoking read.

- Andrew Leland

- Andrew Leland - The Country of the Blind - SFC Carl & Helene Mirowitz Performing Arts Center - St. Louis - Nov 2, 2025 · Showpass

- The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight - Wikipedia

- Instagram - Andrew Leland

- X - Andrew Leland

- LinkedIn - Andrew Leland

This is Season 8! For more episodes, go to stlintune.com

#andrewleland #jewishbookfestival #blindness #beingblind #retinitispigmentosa #disabilityawareness #blindnessmisconceptions #socialperceptionsofblindness #navigatinglifewithblindness

Thank you for listening. Please take time to rate us on Apple podcasts,

Podchaser, or your favorite podcast platform.

00:00 - Untitled

00:14 - Introduction to St. Louis in Tune

03:41 - The Experience of Blindness and Its Impact on Social Interactions

11:15 - Misconceptions About Blindness and Technology

17:02 - Understanding Blindness: Definitions and Perspectives

23:44 - Exploring the World of Blindness and Technology

Arnold

Welcome to St. Louis in tune, and thank you for joining us for fresh perspectives on issues and events with experts, community leaders and everyday people who make a difference in shaping our society and world. I'm Arnold Stricker along with co host Mark Langston who is on assignment. And folks, we're glad that you joined us today.We want to thank our sponsor, Better Rate Mortgage, for their support of the show.You can listen to previous shows@stlintune.com please help us continue to grow by leaving a review on our website, Apple Podcast or your preferred podcast platform. Our guest today is Andrew Leland. He's a writer, audio producer, editor and teacher. He is the has been the finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.His book that we're going to talk about today, the country of the A Memoir at the End of Sight, has been named as one of the best books of the year by the New Yorker, the Washington post, the Atlantic, NPR, Publishers Weekly, and LitHub.He's going to be speaking at the Carl and Helene Mirwitz Performing Arts center at the Millstone campus November 2nd at 7pm we'll talk about that a little bit later on in our interview. Andrew welcome to St. Louis in Tune.

Andrew

Thank you so much for having me.

Arnold

Now, you've been a writer.You are a writer, audio producer, editor, teacher, a bachelor's degree in English Language and Literature from Oberlin and a master's degree from the good old School of Journalism at the University of Missouri. What was the impetus behind this particular book?I know you are going through blindness and why did you decide to write the book during this phase of you going through blindness?

Andrew

I think that the usual reason people there's many reasons why someone might write a book, but I think a common one is that do you want to read a book that doesn't exist in the world?And I was starting to hit a point in my retinal degeneration that felt new and different and so that the disease I have is called retinitis pigmentosa, or rp, and it is very slow. It operates in different speeds in different ways for different people.But I have a kind of a classic version of it, which means it's a very slow degeneration of my retinol cells and my retina. And I have a basically tunnel vision, increasing tunnel vision over the years and then also night blindness.And then as things degrade, my central vision starts to degrade more, too.When I was first diagnosed, even though I had this prognosis of eventual blindness, it took decades for it to really catch up with me And I went through various milestones where I would realize it wasn't really safe to drive at night.And then maybe not safe to drive during the day, but really even all through that, all through my 20s and into even my 30s, it just didn't feel like a big part of my life, like a really important aspect of my experience. It was a thing that I thought about, but I didn't really intrude very much. I didn't use a white cane. I didn't use any assistive technology.I just muddled through. And then it started to intrude, and it started to approach my mid to late 30s, and I just noticed I was missing more things.I was stumbling over things, and driving felt unsafe, and even bicycling felt unsafe. And then once I started using a white cane, that was the real lightning rod moment, because suddenly overnight, I became blind.Even though my vision didn't change, suddenly my social experience of blindness changed. And everybody's kind of treating me differently, from strangers to family members.And that experience felt both difficult and troubling, but also really fascinating and opened up all of these philosophical questions about how everything from how people treat disability and how people conceive of disability, and, like, what perception means and what reading means. And so as those questions started to pile up, it was clear to me that there was a lot of material there and it was. It would support a book.And I started small. I started just with writing short essays or giving talks. And then it really just was this accumulative snowball feeling.Wow, okay, there's enough here to sustain a book. So that's when we dove into the project.

Arnold

Now, you mentioned that this had been something that was an ongoing thing that you knew was going to happen. Is this something that is hereditary or what's the. Have they determined what the cause of this is?

Andrew

Yeah, a couple years ago, I did get a genetic test. So RP refers to a kind of whole constellation of different inherited genetic mutations. There's a number of different mutations that can cause rpm.Sometimes it just can be, like, spontaneous, like a birth defect. So RP is. I think a lot of diseases work that way. Right. Like, it's not one specific, like one particular gene cause, and it's a whole umbrella.And then I found out my particular mutation is called Mauk 1. It's common among Jews. Shout out to the JCC, where I'll be speaking on Sunday and Jews will be. But yeah, so it's like a.It's a particular Jewish flavor of rp, but it's it's equal opportunity. I'm friends with RP guys who are Muslim and Christian and atheist and it takes all colors.

Arnold

So it's, it knows no boundaries.

Andrew

Indeed.

Arnold

Now you mentioned that I, I want to delve into when you started using the white cane, that your friends and family and other people approached you or dealt with you differently. How did they deal with you differently?Because I think this impacts people who have a disability like that or maybe deafness or some other kind of physical, physical impairment. How did that impact you? And talk about that.

Andrew

Yeah, yeah.I think it really calls to mind the idea of passing and which I think is most commonly thought of in racial terms, like Nella Larson's great novel Passing about light skinned black women passing as white, which is a whole separate set of valences, a separate set of ideas around that.But there is a relationship, I think in, in so far as just as blackness heavily stigmatized and particularly was heavily stigmatized and still is anti black sentiment is huge. There is a different related sense of disability stigma that persists to this day.It's interesting to think about it in racial terms because it's very different. And I wrestle with that in the book. I have a tremendous amount of privilege, including racial privilege.But there is a way that like the more disabled I become, the more I realize that there is a stigma. But it's different than racial stigma in some ways because racial stigma, there's a real animus, right?There's like when you think about racism, it's like anti blackness people, it's, it's extremely set against a certain characteristic.Whereas with disability there's this overlay of pity, an overlay of charity, that mask the very real disdain and fear and a lot of this of similar negative and yet anti styled sentiments.And so I started to feel that in a lot of different ways, in terms of strangers, people intruding into my personal space in a way that often was well intentioned.But then as soon as like the bubble of that well intentioned, the sheen, the veneer of that, those good intentions get punctured by my waving it off and saying I'm good, it'll immediately pivot to vitriol and anger and like nastiness or just people, a big one among disability is this fear of fakers. And so I had this guy, I was walking down the street with my cane.I still have central vision, I still have useful vision that I can use to see, but I also still need the cane to avoid all kinds of mayhem and destruction. And I made eye contact with him, this is a scene in the book. And we lock eyes for a second, or he just goes.You can see as though I'm, like, carrying my cane to get a free handout or something. And that's so common.Going back to really, like, the origins of disability history, you've seen this anxiety that people have that they think people are just trying to pull one over on you. And then, yeah, in terms of, like, my friends and family, this is different dynamic, but still a really palpable shift.Some people extremely awkward not knowing how to be around me or being unsure, just like this awkward wedge that comes between us and then. And other people who just delighted me in their ability to ignore it in the way that I want it to be ignored and.But also not ignore them, because when I don't. And it's. It can be a very subtle thing. And one.One of the first revelations I had was that I couldn't blame anybody else and I couldn't really judge anybody else about how they treat disability until I had realized how little I had really considered it.And there was a lot of internalized ableism and having to unpack my own fears before I could start to talk to other people about how they were approaching it.

Arnold

So what do you think is the biggest misconception, conception that people have of individuals who are blind? Is it, how do I help?

Andrew

Or.

Arnold

Yeah, to what extent are you blind and what can you see? Or what do you think it is?

Andrew

I think that the biggest misconception is around ability itself. And I think that blindness, like a lot of disability, becomes this kind of totalizing thing.One example of it is that people will often speak really loudly to blind people. I can't tell you how many times I've heard blind people be like, it's my eyes, actually, not my ears, impairment.And I think that that speaks to just the sense of, this person is a child, right? Or this person is somehow. It's just this, like, snowball effect again of impairment. And you also assume that they're not as intelligent, Right.Or that almost every day people ask me if I can. If I want to take the elevator instead of the stairs. And there's some logic to it, like, they haven't thought it through. But I think if you just.If you think about it for a second, there's no problem with the stairs. I can lock the sign. I can hold onto the railing. Like, my cane helps me feel the stairs. So I'm not angry at people for suggesting that.But I think if you're asking about Misconceptions. It's just this, what one blindness advocacy group likes to call low expectations.And there's just abysmally low expectations for what a blind person is capable of.And another example is you see it on online a lot where there's a lot of blind people posting comments to YouTube or posting comments in message boards. And again, people are like, dude, if you're blind, how are you? How are you even doing this? Is somebody writing it for you?And again, it's understandable if you don't know what a screen reader is like. You would be confused about that.But it doesn't take that much effort to realize that black people are more than capable of doing all kinds of things.

Arnold

When you were mentioning whether I should take the stairs or take the elevator, what came to mind was, no, I think I'll fly.

Andrew

Yes.

Arnold

Yeah, yeah, I appreciate that.Because people don't really look into those worlds of individuals who are disabled because they have the faculties about them and don't really understand that it doesn't have anything to do with intelligence or, you know, the fact that you are blind and I need to speak louder. It doesn't make sense. It's like speaking loudly to somebody who speaks another language.

Andrew

It, it's the same thing.

Arnold

It gets into this. You talked a little bit about technology and there was even in the deaf world there was this ebb and flow and fight between sign and lip reading.And less today than there was in the world of sight or the non sighted. Is there that much like back and forth between braille and technology? I know back in the day when technology wasn't big, you had to use braille.Now what is the emphasis?

Andrew

Yeah, so there was a moment in the 1970s when those circuit TV, CCTV technology started to get cheaper and more widely available. And so you had the first video magnifiers for low vision students and adults.And you could take a book and stick it on your table and you have this machine the size of like an old school PC, but it could. Or like a big screen TV and it would blow up the text on your book. And so you could get work done that way.And then around, and then a little while later you had increasing digital breakthroughs with recorded audio, synthetic speech, and then all the way up to the iPad where you can now today have a blind student.And with enough preparation and the right, as long as they're the textbook manufacturers are doing the right thing, you'll get all of their material digitally and they can have a synthetic voice and a screen reader, reading it out loud.And as a result of that dynamic, you have a lot of teachers, the visually impaired, TVIs and, and others who work with blind people on matters of education and rehabilitation, making the argument that you just rehearsed a little bit, which is that in the era of an iPad that can, like, have anything in the Kindle store, for instance, any book in the Kindle store is essentially accessible to a blind person. Now, do you really need braille? And there are plenty of people who don't read braille.It's especially difficult to get up to a good reading speed as an adult learner, as I found. But a lot of blind people make the argument that there's no true literacy without braille. And one.One thing that they mean by that is that if you only are experiencing text sonically, you're not accessing the morphology of the words, like the actual spelling of the words.And so it's one thing for me as somebody who I can still see magnified print, and I've been a visual reader my whole life, if I lose the rest of my vision tomorrow and then just never learn braille, I'm going to remember that British spellings have a U in it, right? Or that, like, pseudoscience starts with a P and you can even argue how important even is that.But I think, especially if you're talking about a blind student, there is a lot of information in the spellings of words.And then and beyond, even just like knowing how words are spelled, there is something about reading a word tactilely that is much closer to reading it visually in terms of kind of just getting a sense of the structure of a sentence or structure of a word or structure of a paragraph that is so important. As a writer, I care really deeply about close reading and language and how it works.And so I'm actually convinced that braille, I don't demand, I can't demand or even suggest that every blind person learn braille. But I think that it's something that really needs a lot of support and emphasis and funding and celebration.And it's a really important part of a blind person's toolkit, even in the era of all of this, to the old technology. And by the way, braille is itself a technology, just as any print is a technology and readers are technology.But there is a really exciting movement in technology with braille now where you have these refreshable braille displays that are imagined, like a gimbal or an E reader, where you hit the next button and the sort of Ink recapitulates itself into a new page of text. There's braille displays that do the same thing. And so you can really leverage all of the access to accessible textual material with braille.And it's like the best of both worlds.And now there's even more exciting stuff happening with full page braille displays where you can actually have imagining iPad but with refreshable braille that promises incredible advances for tactile graphics. So not to mention just more engagement with text.

Arnold

You mentioned the tactile because I know there is a thought out there that people who are blind, gee, their tactile sense becomes a little better, their hearing becomes a little bit better. Misconception. What is that?

Andrew

Yeah, that's a common one. It's a misconception insofar as if you and I both took hearing tests.Like I'm not going to do better on the hearing test and an audiologist's office because I'm blind. What's not a misconception is that blind people, for obvious reasons, rely more on hearing and touch and so are more attuned to it.And so there's a, there's a, an anecdote I heard from a blind guy where he was standing outside of a bar with his friends and they were all whatever, having a cigarette and he was the first one to notice that the cab had pulled up. Is that because his hearing is better or because like he is focusing more on what is happening in his hearing, in the field of his hearing?And it's the latter, but it's easily mistaken for the farmer.

Arnold

Everyone in St. Louis promises a better mortgage rate, but what you really need to turn that perfect house into your dream home is a better mortgage. At better Rate mortgage, we open the door to so much more.Whether you're purchasing your first home or taking cash out to make your dream home even dreamier, our door is open. Come on in and get started. Today we'll show you how.Call Sean directly at 314-375-3293 or online@betterratemortgage.com Remember, at Better Rate mortgage, a better rate is just the beginning. Don't betterratemortgage.com MLS ID 2401335 an equal housing lender. Now, how do you define blindness?There is a definition of blindness by Kenneth Jernigan and he is known for the National Federation of the Blind leading that for a long period of time. And for some people, they think you're, you totally can't see.You're either Blind from birth or you lose your sight along life, and there's some difficulties and differences there in the definition and what people perceive who are just, who are sighted, people that live in the world. How do you define blindness?

Andrew

Yeah, I'm definitely influenced by the National Federation of the Blind, the nfp.And I think one thing that's really important and useful about their definition, which is more capacious than you might think, I think the way they define it currently is that if you rely on an assistive technology, whether it be a guide dog or a white cane or one of those screen magnifiers I described, or a screen reader on your computer, if any of those things is necessary for you to get through your day, get through the day of school or get through a day of your job, or just live a life that you want to live, then you can be in the club, then you're blind. And I think that is such an important definition because of this really powerful impulse towards denial.It's just, you just again and again and it actually shockingly has very little to do with how much vision you have.Because there's people who are totally blind who can be in denial, and then there's folks in my camp with the sort of low vision crew where it's very common to be in denial. But in both cases, it's incredibly dangerous, both emotionally, spiritually and physically to be to live in denial of your blindness.But because of that stigma we were talking about, it's also, there's an incredibly powerful pull towards Denal Arrow and just saying, you know what, I'm not, I don't need this king, like, and make everybody choose to be funny with it. It's going to make it awkward. I'm just gonna, I'm just gonna go without it. And then you can imagine the, the real problem with that.Like I said, there's, it's not just about the physical risk of like cruising outside without your cane. There's also just like a sort of spiritual death that can happen. You just, you can't live a full life with it.So I think that's why it's so important to say, you know what, even if you can see when the light change to red, but if you're still like needing a magnifying glass to read any print at all, or if you're still like, need that white cane to avoid tripping over a fire hydrant, yes, you can call yourself blind. And the power of that is that then you can accept that, you know what, it's not weird or Bad that I am a white cane. Like, I'm blind.Of course I need a white cane. And there's just, like, a liberation that comes with that.That has been one of the most powerful, powerfully transformative experiences of my adult life. Is coming to accept that and realizing how much more I can do after accepting it than I could before when I was keeping it very compartmentalized.

Arnold

Talk about that acceptance process, because it's a recalibrating of who you are and what you can and cannot do.It's much an elderly person who can no longer drive because they shouldn't be behind the wheel because they're going to put themselves and other people in danger. Or very similar to someone who might have a mental illness who says, I feel good now and I'm going to stop taking my medication. Things like that.How did you recalibrate? How did you get to that point?

Andrew

Yeah, really, the process of reporting the book was a process of talking to as many different blind people as I could and as many different arenas as I could. And the way that my book is structured, it's around different aspects of this experience that I encountered.There's a chapter about masculinity and gender and the blindness affects these sort of gender roles, and a chapter on technology and a chapter on identity politics and politics more broadly. And each of those, I got to meet with all kinds of different blind people who are super engaged in the debates surrounding those ideas.And after a while, I started to. I didn't agree with everybody. There were some people who really rubbed me the wrong way.But even that was useful information was like, okay, I'm like, entering this big family of blind people. And some of them, like, any family. Maybe I'll see you at Thanksgiving. But it's not.And then other people who are like, I love dearly and I now count among my closest friends and who have taught me so much and continue to teach me so much. And I think a lot of that process has come from finding blind role models. And. And I think they're.One of the tragedies in a lot of blind people's lives is the tragedies of blindness. It's just that they only have been exposed to people who have that exceedingly low expectation view of blindness. And so then they internalize it.And they never find a blind person who can say, you know what? Crab your cane is going to go get a burger, and we're out. There's no sighted people needed. We're just going to. I know where the bus stop is.I Know where the burger place is, let's go. And that experience is so important. And too many blind people don't get it just because they end up getting pigeon bones in the world.Without folks who understand how expansive of an experience blindness can be.

Arnold

Or crossing the street like you were going to pick up your son. And the woman at the light said, okay, we're going to walk. We're going to cross now. And yes, we are.

Andrew

Yeah, yeah, yeah. And a lot of that confidence that I got in crossing the street like that came from my time at a lioness training center.The one I visited was in Littleton, Colorado, New greater Denver called the Colorado center for the Blind.And they, they, it's a school, but instead of physics and Latin and algebra, they teach you orientation and mobility, walking around the city independently. And they teach you cooking skills of how to fry an egg on a gas stove.And everybody wears vivid clothing, sleep shoes where it's nine to five every day, so you see nothing, no matter if you're low vision like me or somebody who's totally blind, everybody's on the same playing field there.And there's a braille class and a tech class, and a couple weeks in a center like that, you get a lot of confidence in looking at life as a blind person. That's a good one.

Arnold

I can imagine being in a place like that has individuals who are in a variety of blindness and they are learning techniques. And like you said, there's some people I really got a lot of good information from. I.Some I got bad information from, or I'll do that or I won't do that. And how long were you there at Eden Littleton?

Andrew

The program is supposed to be nine months. And so I cheated a little bit. And I went and did like the journalists crash course.Like, I don't think they generally let people come for just a couple weeks. But I only went for a few weeks because I just. Part of it was during COVID and I was. I have a book deadline at the. Right.And the other part, I was expanding the next year for New Yorker magazine. And so I went back for an additional two weeks. But I think ideally I would have gone for nine months.I think there's still so much more for me to learn.

Arnold

So other than the white cane or learning how to fry an egg on a gas stove or things like that, what are some of the other what I would call daily intricacies that someone has to reprogram themselves for?

Andrew

Yeah, I mean, blind people love their technology. And one of the reasons for that is that if you think about, like, where the barriers are around blindness, it's information, right?Because so much of information is visual, whether it's like, street signs or books or videos or all that stuff.So I think a big one for me and for every blind person is figuring out your workflow around reading the news, reading the book, reading books you want to read, depending on what your work is like. For me, I'm a professor of writing and journalism, and how am I going to teach my class? How am I going to project stuff on the screen?And all that stuff is possible, but it definitely takes some computer knowledge.And one thing that really struck me in researching my book was just how every blind person, to some degree or another, ends up becoming, like, a computer hacker or at least like a computer enthusiast. And there's just, like, a level. We live in an age when more people than ever before have knowledge of how software works.But, man, blind people are overrepresented in that world. If you just.If you hang out on these news groups or listservs or different online meetups, even, like, blind people whom you would think would have no reason to be geeking out over multiple operating systems and running beta tests and different software, like, they're doing it. And the reason is that they have to, because software is constantly breaking and is inaccessible to blind people. And it's really.We don't have an option, Most blind people don't have an option of just saying, oh, I'll try a different tool here. Because often a stream mirror is only going to work with one type of program, and they push an update and it breaks.And so blind people really are hackers.

Arnold

I imagine you were really pretty pleased when you were a finalist for the 2024 Pulitzer and the memoir.

Andrew

I was, yeah. It was awesome.

Arnold

That it's your journey, and your journey continues. Is there going to be a second part to this or.

Andrew

Another book you asked? I think so. I'm still. I'm at the point now where I only want to write a book if it in something that I feel like I have to do because I don't know.I've read enough books out there that are just. They feel like they're written because somebody felt like they should write a book, and I don't want to do that.But also, I feel like I just wait until I have this, like, burning desire, like, I have to write it like I did for this book. I might be waiting a very long time. So I'm trying to split the difference between what is, like, the existential demand to write a book.And what is just me contriting something because I want to continue calling myself a writer.But in honesty, that writing this book, it opened up a lot of doors onto ideas that I explored to the fullest that I could and the constraints of my first book. But I do feel like there's a lot more about disability and blindness and accessibility that I still want to explore.Give me a couple years, but I would like to write another one.

Arnold

Do people follow you on social media and asking like, okay, where are you at with this now?Or other blind people or other people going through similar situation that you have and seeking some advice or asking inquiring about how you are dealing with it?

Andrew

Yeah, for sure I'm not that hard to find online and that, yeah, that's been a super cool part of this process.It's just like this long tail of readers who the book came out in the summer of 2023 and I'm still every week hearing from folks who sometimes it's like a blind person, sometimes it's somebody who like just got diagnosed, sometimes it's somebody who's a relative of a blind person or I've heard beautiful stories of people's memories of their grandparents or parents or siblings.And yeah, I feel like, you know, my name is now out there attached to this book and as a result like my email address is on my website and I just, I love getting messages from folks.

Arnold

We've been talking to Andrew Leland.He's the author of the country of the A Memoir at the End of Sight and he's going to be at the Carl and Helene Mirowitz Performing Arts center on the Millstone campus.And that will be November 2nd at 7:00pm you can get more information at jccstl.com, jccstl.com Andrew, thank you very much for talking to us on St. Louis in Tune today.

Andrew

Oh, my pleasure. This is a super great conversation and I'm excited to return to Missouri.

Arnold

That's all for this hour. Thank you for listening.If you've enjoyed this episode, you can listen to additional shows at STL and consider leaving a review on our website, Apple Podcasts, podchaser, or your preferred podcast platform. Your feedback helps us reach more listeners and continue to grow.I want to thank Bob Berthiselle for our theme music, our sponsor, Better Rate Mortgage, our guests Andrew Leland and co host Mark Langston. And we thank you folks for being a part of our community of curious minds.St. Louis in tune is a production of Motif Media Group and the US Radio Network. Remember to keep seeking, keep learning, walk worthy and let your light shine. For St. Louis in Tune, I'm Arnold Stricker. It.

I'm the author of The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight, which was a finalist for the 2024 Pulitzer Prize in memoir and named a best book of the year by the New Yorker, the Washington Post, the Atlantic, NPR, and others. I've contributed to the New Yorker, New York, the New York Times Magazine, and other publications with New York in their names. I'm a contributing editor of the Believer magazine and I used to make the Organist podcast. I've also contributed audio journalism to Radiolab and 99 Percent Invisible. Right now I'm the Koeppel Fellow in Journalism at Wesleyan University.